Threads of the Divine: Exploring Japanese Buddhist Altar Textiles

Buddhist altar cloths, known as uchishiki, are remarkable examples of Japanese textiles that have adorned temples and private households for centuries. These cloths, often characterized by their intricate embroidery, delicate finger-picked tapestry, or luxurious brocade, exhibit exceptional artistry and reflect the unwavering devotion of their creators. They often feature auspicious symbols, religious motifs, or patterns that hold deep spiritual meaning.

While there have been various publications exploring Buddhist artifacts, including texts focused on the kesa (monk's robe), this article aims to shed light on the lesser-researched uchishiki altar cloths used to adorn both public temples and private butsudan (Buddhist altars). This article focuses specifically on uchishiki cloths made before the Showa period (before 1926).

In its literal translation, uchishiki means “strike spread out,” tracing its origins back to 2500 years ago in India. During that time, it referred to a fine cloth that was “spread out” for Shakyamuni Buddha to sit on while delivering his teachings. His followers would then “strike” their foreheads on the ground as a gesture of reverence. This practice involved using high-quality fabrics as both temple adornments and garments for monks in India and neighboring regions.

When Buddhism was introduced to Japan in the 6th century, the tradition of using specialized temple textiles was also brought along. Laypeople in Japan began to donate such textiles to temples, marking the beginning of a significant cultural practice. For instance, upon the passing of a woman, it became customary to donate her most cherished kimono or obi (sash) to a nearby Buddhist temple, accompanied by prayers to comfort her soul. These garments would then be carefully disassembled, cut into fragments, and meticulously resewn into various types of temple textiles.

This act of donating temple textiles was considered a devout deed that held spiritual significance. It was believed to help individuals accumulate spiritual merit and distinction. Offering an uchishiki to a temple was a way to pray for the departed soul to be purified and become an ancestral spirit, eventually being reborn into the world.

Some uchishiki featured linings inscribed with dedicatory kanji script, often including details such as the Buddhist name of the deceased, the commemoration date, the donor's name, and well-wishes for the departed soul. This practice of textile donations was widespread across all segments of Japanese society. The earliest recorded instance dates back to 756, when Empress Komyo donated Emperor Shomu’s textiles to Todai-ji temple in Nara, 49 days after his death.

Most uchishiki are not typically found in large temples but serve as important adornments in private Japanese homes, specifically within the butsudan, or household Buddhist shrine. The concept of the butsudan traces its origins to early Buddhist traditions in India, where roofed platforms were built to house devotional items. In Japan, aristocratic devotees began constructing private temples known as jibutsudo—small, freestanding temples housing a Buddha statue and ancestral tablets. During the Heian period (794–1185), wealthy families incorporated these temples into their homes, creating butsuma, or dedicated altar spaces, for religious observance. Commoners, too, began constructing smaller versions of butsudan, housed in wooden cabinets.

The practice of installing a butsudan in one’s home became widespread during the early Edo period (17th century) after the Shogunate issued a directive known as terauke-seido, which mandated that families affiliate with Buddhist temples. In return, temples commemorated family ancestors during memorial services. Thus, the butsudan became a focal point for domestic spirituality—a uniquely Japanese phenomenon with little parallel elsewhere in the Buddhist world.

In recent decades, however, the tradition of the butsudan has declined. Many families no longer maintain them, and many local temples face closures due to declining community engagement. Consequently, the use of uchishiki and the art of temple textile donation have also diminished. This shift reflects changing societal values and a broader move away from traditional religious practices.

Nevertheless, there is a growing appreciation for uchishiki among museums, collectors, and scholars. While practicing temples may distinguish between different types of altar cloths—such as mizuhiki and tocho—many institutions now use uchishiki as an umbrella term for various Buddhist altar cloths.

Notable contributions to the study of uchishiki include works by Peter Sinton in Daruma magazine and Helen Loveday’s book Japanese Buddhist Textiles. Museums such as the Baur Foundation in Switzerland and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston house significant collections of uchishiki, which range from brocade masterpieces to rare slit-tapestry and embroidered examples.

The sizes of uchishiki vary greatly—from small triangular types used in household butsudan to large rectangular versions designed for temple use. Smaller cloths may be diagonally draped over a table, with the ornate corner hanging down as a focal point, while larger ones are placed beneath Buddha statues or across sacred furnishings. Some smaller uchishiki feature plain white linings, typically made of handspun cotton or hemp, while others display full surface designs.

A variety of textile techniques were used in crafting uchishiki. Luxurious brocades made with gilt-paper threads dominate surviving pre-1900 examples. Nishiki kinran and ginran brocades—woven with gold or silver threads—were commonly used. The silk ground might be twill or satin, supplemented with wefts of flat or twisted gilt paper threads. These materials were often produced in the Nishijin district of Kyoto, which refined techniques originally imported from China. Initially used for Noh costumes, these opulent textiles became popular for kesa and altar cloths. In modern times, imitation threads have replaced real gold and silver.

Design motifs in uchishiki include dragons, clouds, phoenixes, peonies, lotus flowers, and stylized rocks—each imbued with symbolic meaning. Auspicious clouds, for instance, signify divine blessings and often form a bridge between celestial and earthly realms. Peonies symbolize wealth, lotus flowers spiritual purity, and the phoenix rebirth.

In slit-tapestry (tsuzure-ori), weavers employed discontinuous wefts to produce painterly designs with remarkable intricacy. These cloths resemble hand-painted scrolls, thanks to the subtle transitions and vibrant color gradations. The layout of these designs often divides the cloth into upper celestial and lower earthly zones, separated by swirling clouds or stylized mountains.

Embroidery, too, played a major role in uchishiki ornamentation. Shishu, or silk thread embroidery, added colorful patterns, while koma-nui, a couched embroidery technique using gold and silver threads, provided glimmering relief. Some rare examples were even embroidered on wool or imported red broadcloths.

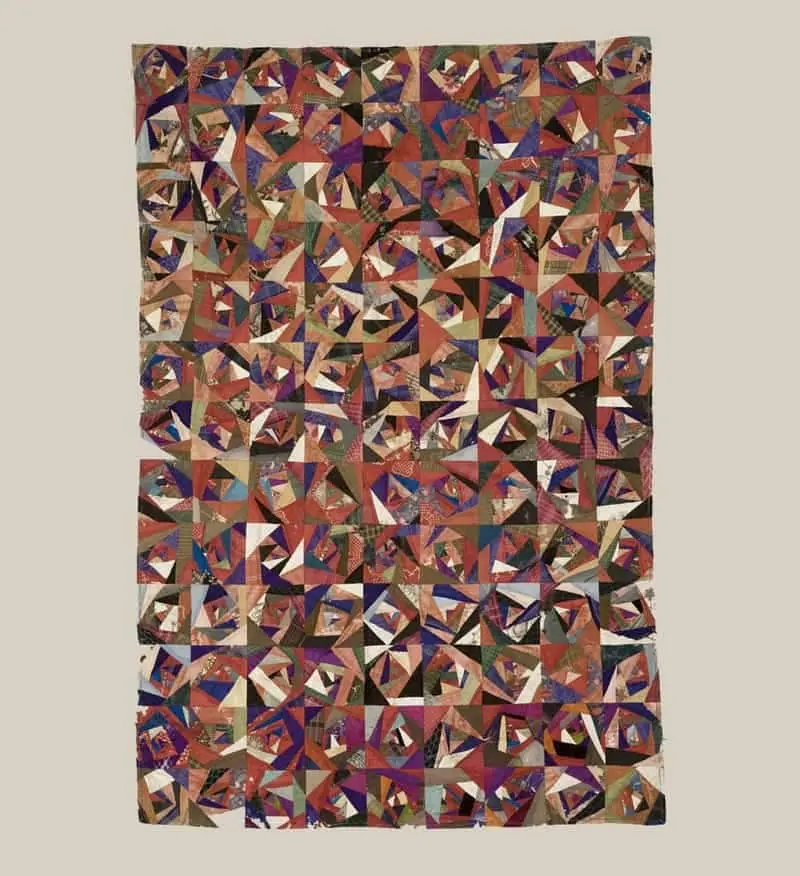

A rarer form of uchishiki is constructed from patchworked kimono silk—a distinct technique from the patchwork used in monk’s robes. These examples display a deep sensitivity to pattern and color, often mixing fabrics of different texture and origin. The white reverse lining, in addition to stabilizing the structure, also carried symbolic significance. In times of mourning, uchishiki were often turned inside out to reveal the plain white side, emphasizing spiritual reflection and reverence.

In sum, uchishiki are not merely decorative cloths; they are vessels of memory, belief, and aesthetic devotion. Their creation and use span a broad spectrum of Japanese social history—from aristocratic patronage and household rituals to modern museum appreciation. As both spiritual offerings and textile masterpieces, uchishiki stand as enduring symbols of devotion, artistry, and cultural continuity.

.avif)