The Art of Tsutsugaki: Japan's Freehand Paste-Resist Dyeing Tradition

Among the many sophisticated textile techniques that have flourished in Japan, tsutsugaki (筒描) stands as a distinctive method of resist dyeing that involves drawing rice-paste designs on cloth, dyeing the cloth, and then washing off the paste. This remarkable technique, which emerged as both an artistic expression and practical necessity, has produced some of Japan's most visually striking and culturally significant textiles. From humble household linens to elaborate ceremonial futon covers, tsutsugaki represents a unique fusion of artistic creativity and domestic functionality that has captivated textile enthusiasts and cultural historians alike.

The Technical Foundation of Tsutsugaki

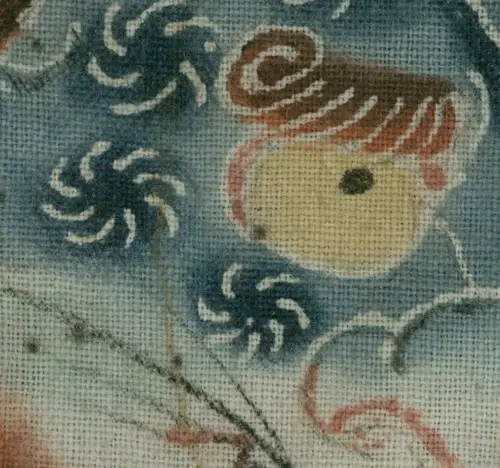

The fundamental process of tsutsugaki is deceptively simple yet requires considerable skill to execute effectively. The rice paste is typically made from sweet rice, which has a high starch content and is therefore rather sticky. The paste is applied through a tube (the tsutsu, similar to the tubes which are used by bakers to decorate cakes), a technique that gives the method its distinctive name—literally meaning "tube drawing."

The application process is remarkably similar to applying icing on a cake, where artisans squeeze the paste out of a bag. This analogy, while simple, captures the essence of what makes tsutsugaki so distinctive among Japanese textile arts. Unlike katazome, which uses stencils to apply resist paste, or the more refined yuzen technique employed on silk kimono, tsutsugaki is entirely freehand, allowing for a spontaneous and personal quality that reflects the individual artisan's skill and artistic vision.

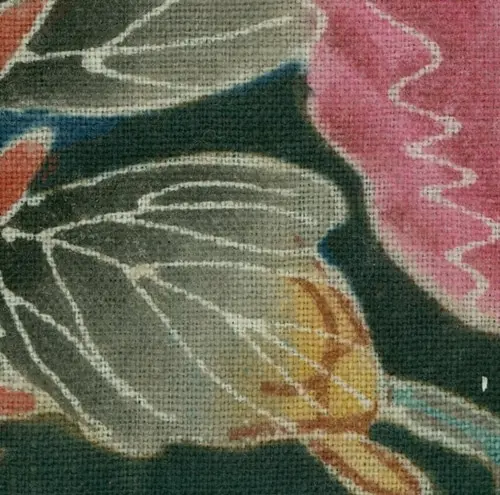

The resist paste serves as a barrier during the dyeing process, preventing the dye from penetrating the areas where it has been applied. Once the paste has dried completely, the fabric is immersed in dye—most commonly indigo—creating the characteristic contrast between the undyed areas protected by the paste and the deeply colored background. After dyeing, the paste is carefully washed away, revealing the final design as light areas against the darker dyed ground.

Historical Development and Cultural Context

Research has discovered that natural indigo dye was used in Japan as far back as the 5th century, competing for popularity with red and brown madder dyes which were used to color all sorts of objects. However, the development of tsutsugaki as a distinct technique occurred much later, emerging during a period of significant social and economic change in Japanese history.

Since the 16th century, tsutsugaki textiles were made to celebrate major events occurring during life, establishing the technique's important role in Japanese ceremonial and domestic culture. The timing of tsutsugaki's development coincided with broader changes in Japanese society, including the growth of a merchant class and the increasing availability of cotton as a textile fiber.

The technique emerged during a period when females could make supplemental income by the sale of their domestic labor to outsiders, resulting in the birth of a cotton fabrication cottage industry. This economic dimension was crucial to tsutsugaki's development, as it provided both the motivation for skill development and the means for its dissemination throughout Japanese society.

The democratization of textile production that tsutsugaki represented was significant in a society where the most elaborate textile techniques were traditionally confined to the upper classes. Unlike the complex embroidery or yuzen painting that required years of formal training and expensive materials, tsutsugaki could be learned and practiced by ordinary women in their homes, using relatively simple tools and locally available materials.

Futonji: The Ceremonial Canvas

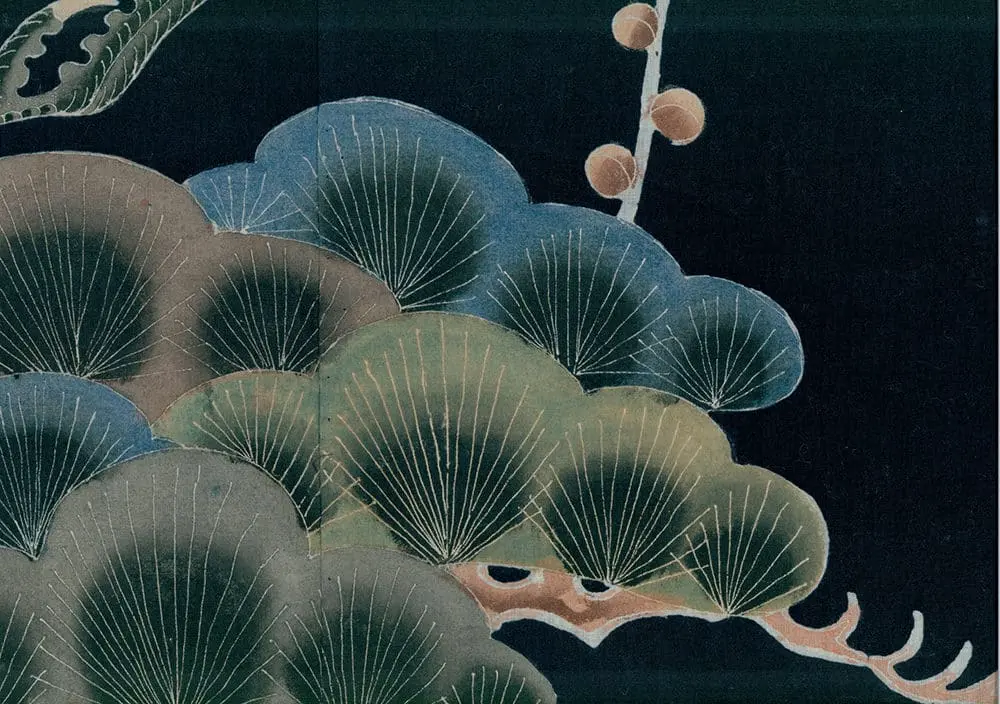

Perhaps nowhere is the artistry of tsutsugaki more evident than in the creation of futonji—decorative futon covers that served both practical and ceremonial purposes. The traditional Japanese bedding set, known as a futon, typically consists of a padded mattress and a quilted bedcover, the latter often incorporating a decorated cover that would have been made as part of a bride's trousseau.

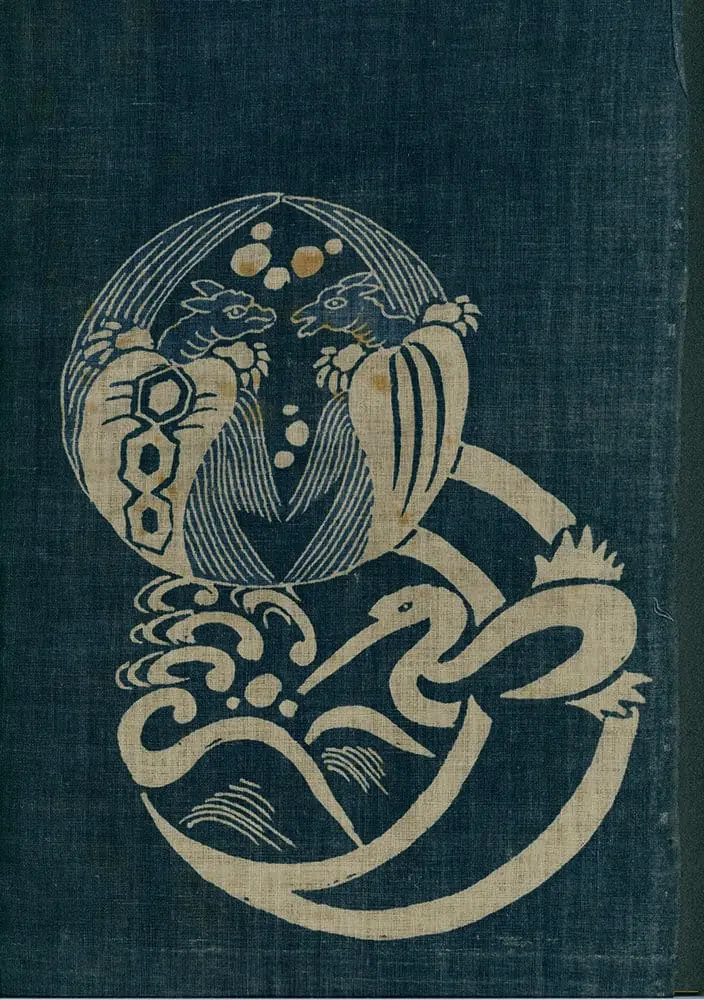

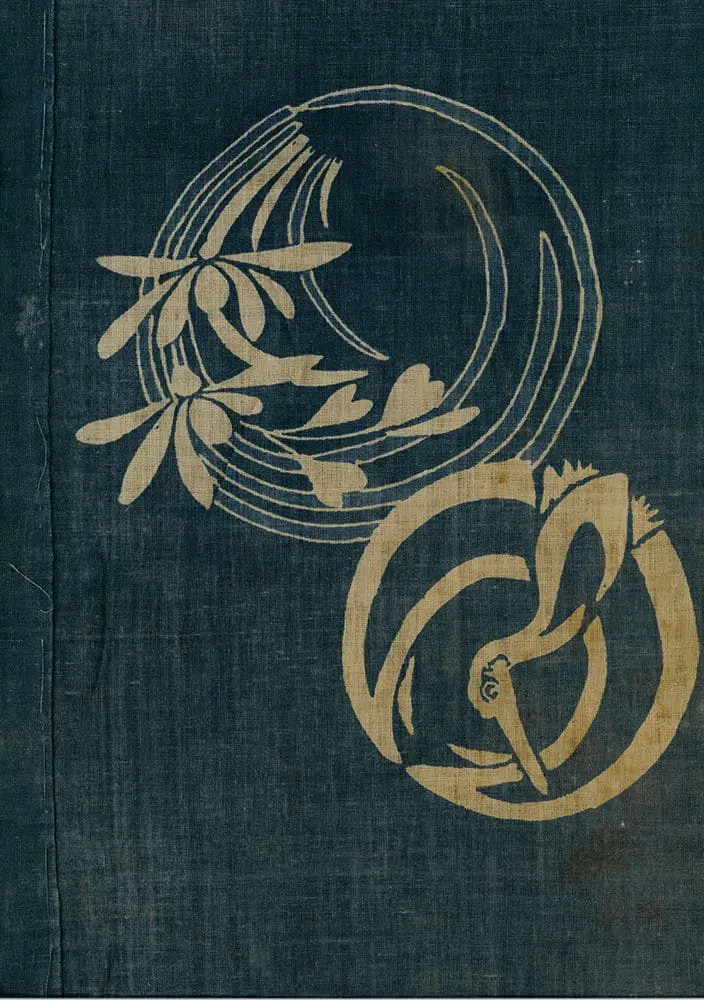

These elaborately decorated covers transformed the humble futon into a canvas for artistic expression and cultural meaning. A typical tsutsugaki futonji might feature pine, crane and turtle motifs, where the pine is ever green, lives to be a thousand years old, and is the dwelling place of the gods, while the crane and turtle frequently appear together as symbols of longevity. Such motifs were not merely decorative but carried deep cultural significance, serving as visual prayers for health, prosperity, and longevity.

The creation of futonji represented a significant investment of time and skill, often taking months to complete. These covers were frequently made by women as part of their preparation for marriage, demonstrating both their textile skills and their understanding of cultural symbolism. The finished pieces served as important household textiles that would be displayed during special occasions and passed down through generations as family heirlooms.

The bold, graphic quality of tsutsugaki futonji designs reflects the technique's inherent characteristics. The freehand application of resist paste encouraged bold, flowing lines and simplified forms that could be effectively executed without the precision required by more refined techniques. This aesthetic quality, born from technical constraints, became one of tsutsugaki's most distinctive and appealing features.

Artistic Characteristics and Design Elements

Tsutsugaki is a freehand dyeing method that produced one-of-a-kind textiles, and this uniqueness is perhaps its most defining characteristic. Unlike mechanically reproduced patterns or even hand-stenciled designs, each tsutsugaki piece bears the distinctive mark of its creator's hand, making every textile a unique work of art.

The technique's aesthetic is characterized by bold, flowing lines and simplified forms that work effectively within the constraints of the paste-resist process. Common motifs include natural elements such as flowers, birds, and trees, as well as mythological creatures like dragons and phoenixes. These designs often carried symbolic meaning, with each motif carefully chosen to convey specific wishes or blessings.

The contrast between the undyed areas and the deep indigo ground creates a striking visual effect that has made tsutsugaki textiles highly prized by collectors and museums. The technique's bold graphic quality gives it a contemporary appeal that transcends its historical origins, making antique tsutsugaki pieces highly sought after in today's design-conscious world.

The scale of tsutsugaki designs tends to be bold and dramatic, well-suited to the large format of futon covers and other household textiles. This monumentality, combined with the technique's inherent spontaneity, creates textiles that are both visually striking and emotionally engaging.

Materials and Regional Variations

The materials used in tsutsugaki production were typically local and readily available, reflecting the technique's roots in domestic textile production. Cotton was the preferred base fabric, as it took indigo dye well and was more affordable than silk. The cotton used was often hand-woven, giving the finished textiles a distinctive texture that enhanced their visual appeal.

Indigo was the predominant dye used in tsutsugaki, chosen for both practical and aesthetic reasons. Indigo's deep, rich color provided excellent contrast with the undyed areas, while its lightfastness ensured that the textiles would maintain their appearance over time. The widespread cultivation of indigo in Japan made it readily available to textile producers throughout the country.

Regional variations in tsutsugaki techniques and designs developed as the craft spread throughout Japan. Different areas developed their own stylistic preferences and technical approaches, creating a rich diversity within the overall tradition. These regional characteristics were often influenced by local cultural preferences, available materials, and the specific needs of different communities.

Cultural Significance and Social Function

Tsutsugaki textiles served important social and cultural functions beyond their practical utility. As ceremonial objects, they marked important life transitions and celebrations, serving as visual representations of cultural values and aspirations. The creation of these textiles was often a communal activity, with knowledge and techniques passed down through generations of women within families and communities.

The technique's accessibility made it an important means of artistic expression for women who might otherwise have had limited opportunities for creative outlet. The creation of tsutsugaki textiles allowed women to develop and demonstrate their artistic skills while contributing to their family's material well-being and cultural heritage.

The symbolic content of tsutsugaki designs reflects deep connections to Japanese cultural and spiritual traditions. The frequent use of auspicious motifs such as cranes, turtles, and pine trees demonstrates the technique's role in expressing hopes and prayers for good fortune, longevity, and prosperity.

Legacy and Contemporary Appreciation

Today, tsutsugaki textiles are recognized as important examples of Japanese folk art, collected by museums and private collectors worldwide. Their bold graphic quality and unique aesthetic appeal have made them particularly popular among contemporary designers and textile enthusiasts who appreciate their combination of artistic sophistication and cultural authenticity.

The technique's influence can be seen in contemporary textile arts, where artists have adapted tsutsugaki principles to create modern interpretations of this traditional craft. The emphasis on freehand drawing and resist dyeing continues to inspire textile artists who value the spontaneity and individuality that these techniques allow.

Museums and cultural institutions have played an important role in preserving and documenting tsutsugaki traditions, ensuring that this remarkable technique remains accessible to future generations. Through exhibitions and educational programs, these institutions have helped to maintain appreciation for the skill and artistry involved in creating these unique textiles.

.avif)