The Artisan and the Machine: Distinguishing (and Combining) Kata-Yuzen and Silk-Screening.

In early20th-century Japan, kata-yuzen and silk-screening were two prominent silk patterning techniques, each with its own distinct process. While these techniques differ in their application methods, they often produce results that can be challenging to distinguish at a glance, and it is due to these similarities in visual effects that they are being discussed together in this publication.

Process:

Kata-yuzen was a variation of the traditional yuzen dyeing technique but used stencils to apply the resist paste. Instead of hand-painting intricate designs directly onto the fabric, artisans would use stencils (kata)to guide the application of rice-paste resist. The paste protected areas of the fabric from dye penetration, enabling the creation of multi-colored, highly detailed patterns. Each color required a separate application of resist dye, making the process meticulous and labor-intensive. This allowed for the production of complex and nuanced designs while preserving the handmade quality associated with traditional yuzen.

Silk-screening (shirukusukurīn), introduced from Western printing technology, used a mesh screen to transfer ink or dye onto the fabric.By blocking out areas of the screen, specific designs could be printed onto the fabric in bold, clean patterns. The process involved spreading dye over thescreen with a squeegee, which pressed it through the unblocked areas of the mesh. Silk-screening was faster and more efficient compared to kata-yuzen, allowing for rapid and repeatableproduction of fabrics, which became increasingly popular in the context of Japan's industrialization and modern fashion demands.

Results:

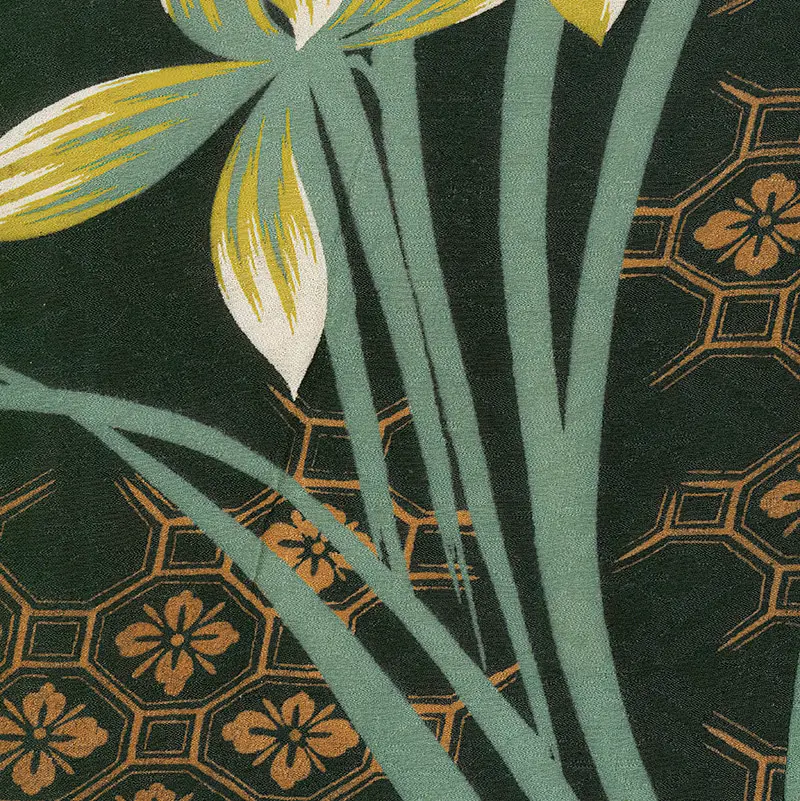

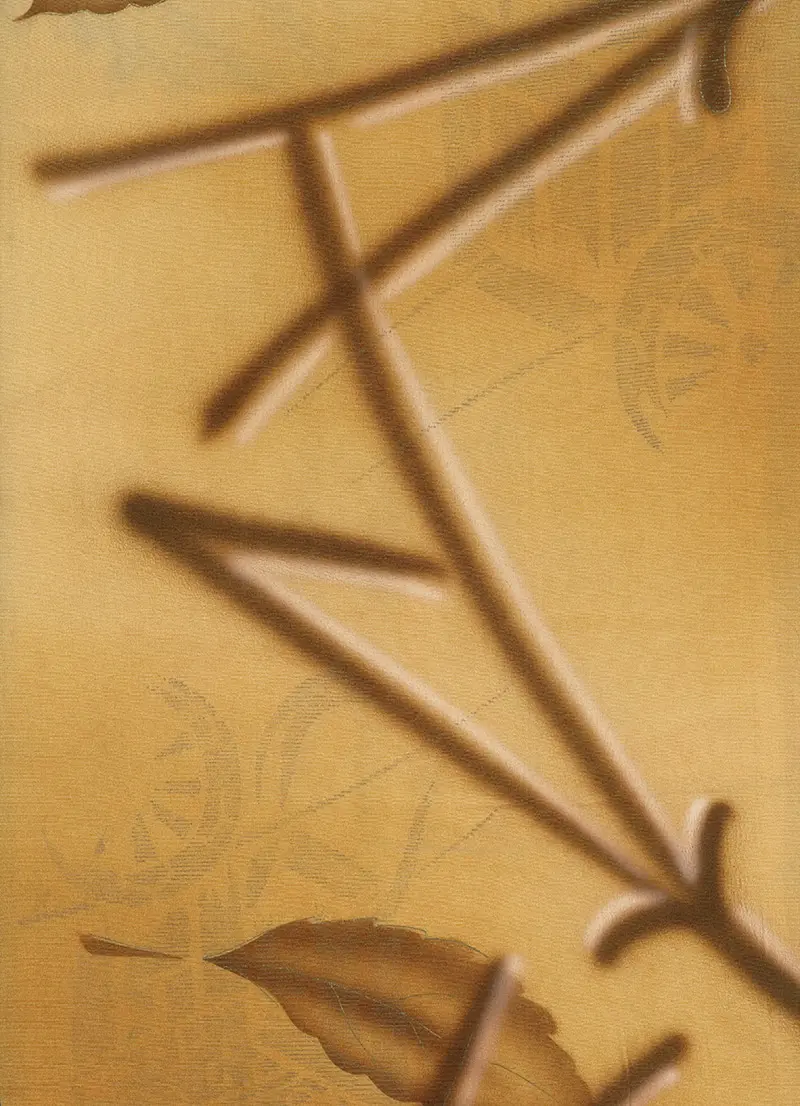

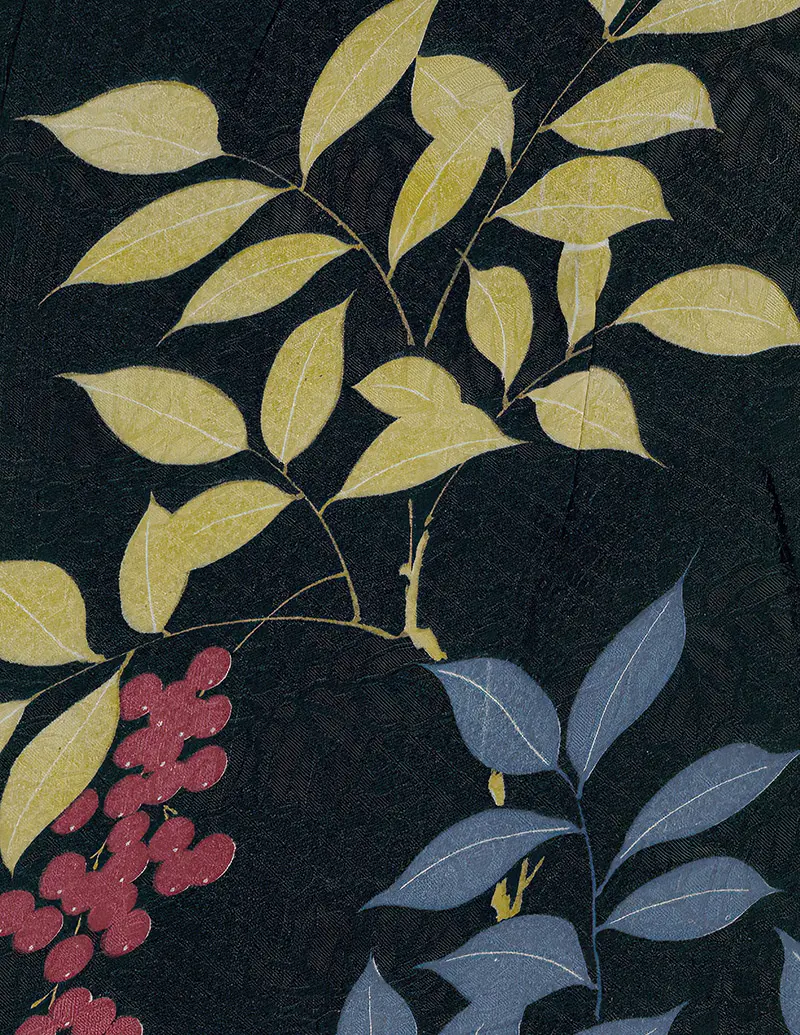

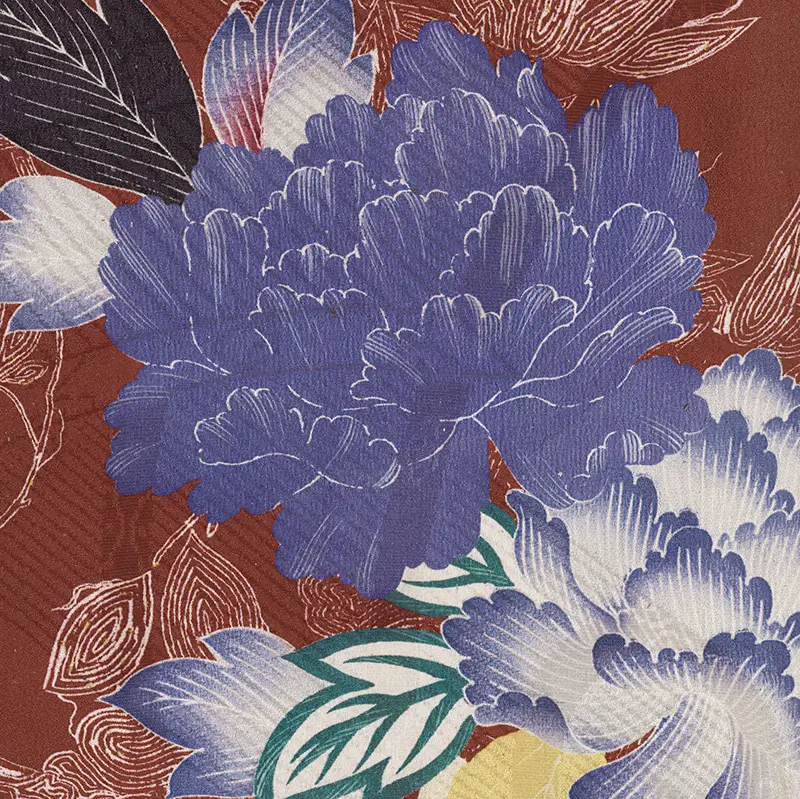

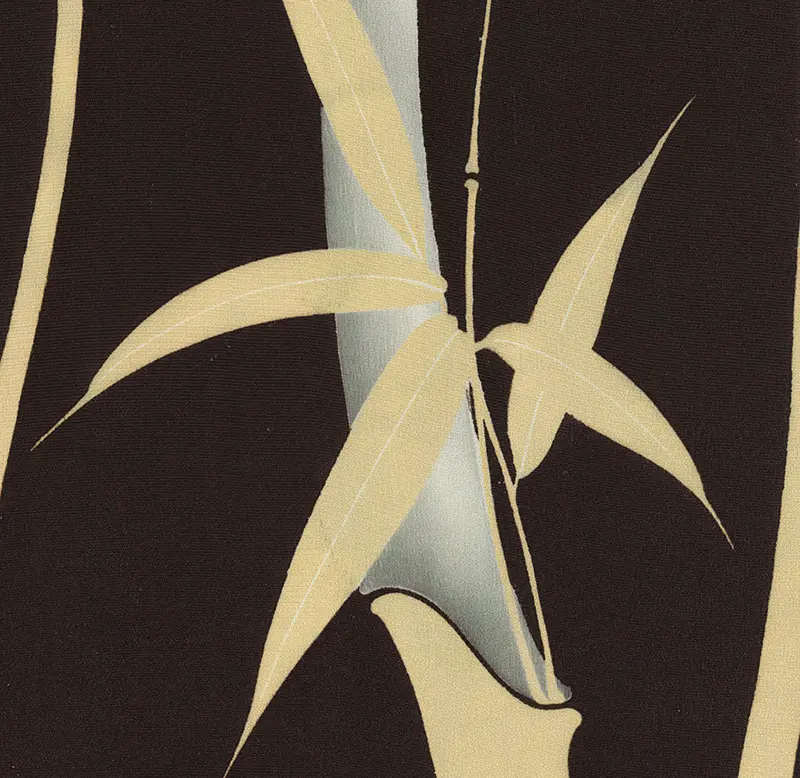

The use of stencils in kata-yuzen produced designs with fine, intricate details and soft transitions between colors. The technique allowed for more organic patterns with subtle variations in color and tone. Each application of resist and dye created a layered, nuanced design, often with delicate outlines and shading. The handcrafted appearance of kata-yuzen garments gave them a refined aesthetic, perfect for formal and luxury kimono and haori.

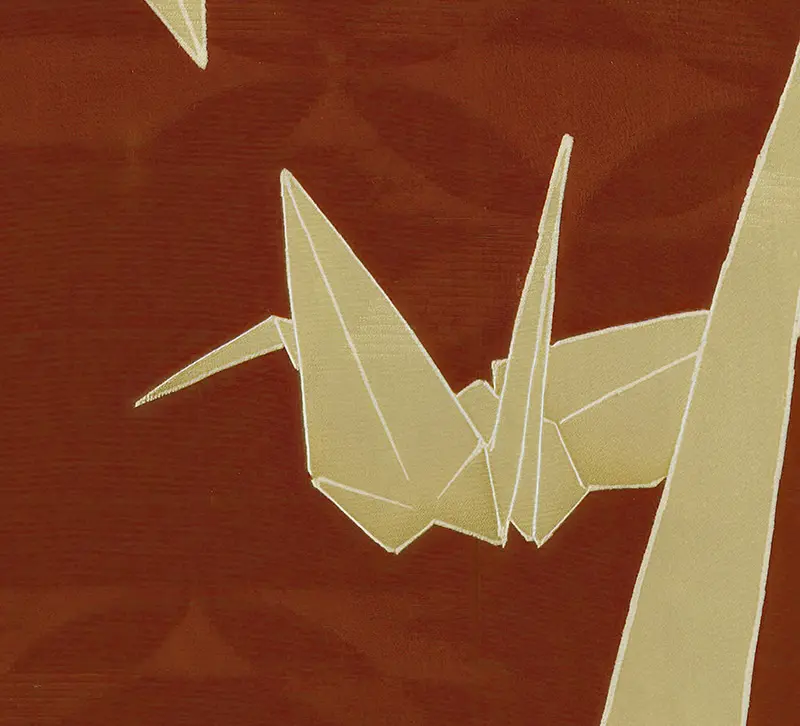

Silk-screening, by comparison, resulted in sharper, more uniform patterns with solid blocks of color. The mesh screen used in silk-screening allowed for the rapid transfer of bold, graphic designs, making it well-suited for modern, abstract, and geometric motifs. While the patterns were less detailed than those created through kata-yuzen, silk-screening enabled consistent and repeatable designs, ideal for large-scale production. The contrast between the two techniques was apparent in the final look: kata-yuzen patterns appeared more intricate and traditional, while silk-screening was modern, vibrant, and mass-producible.

Kata-yuzen and silk-screening likely were used together on the same silk haori fabric, especially during the early 20thcentury when textile artists and manufacturers in Japan were experimenting with various techniques to achieve unique and complex designs. This blending of methods allowed for the creation of textiles that maintained the beauty and detail of kata-yuzen while benefiting from the efficiency and new visual possibilities provided by silk-screening. Thus, it was not uncommon to see fabrics where elements like detailed motifs(e.g., florals or geometric patterns) were kata-yuzen-dyed, while background patterns or broader design areas were applied using silk-screening.

History:

Kata-yuzen evolved from the traditional yuzen technique, which had been practiced in Japan since the Edo period (1603–1868). The kata-yuzen process emerged as a way to preserve the essence of yuzen dyeing while simplifying and speeding up production. It was a popular method for producing luxury textiles well into the 20th century, especially for garments that required fine detailing.

Silk-screening, on the other hand, was a relatively new technique in Japan during the early 20thcentury, imported from the West as part of the country's modernization efforts. It quickly became the go-to method for producing textiles en masse. As the demand for more affordable, ready-to-wear kimono and haori increased, silk-screening provided an efficient solution, particularly during the Taisho (1912–1926) and early Showa (1926–1940) periods.

.avif)