Wrapping Meaning: The Symbolism and Artistry of Japanese Fukusa Gift Cloths

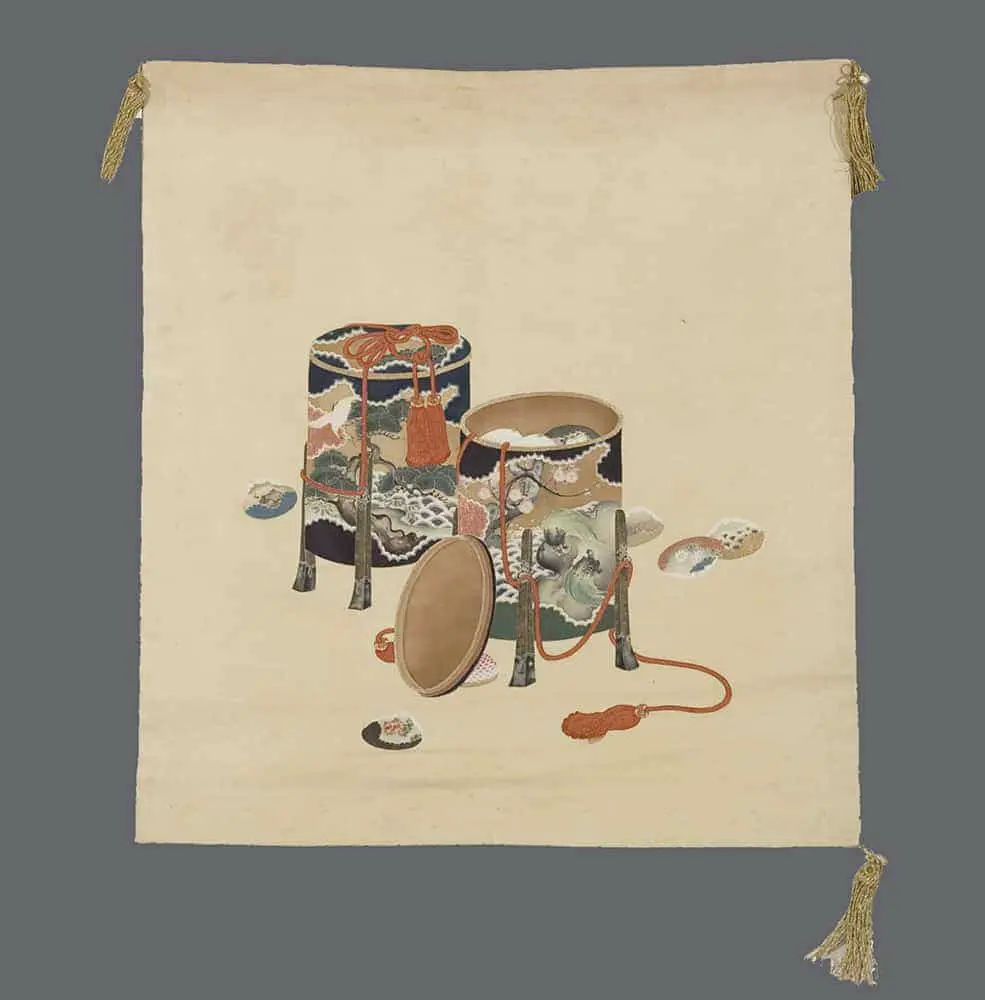

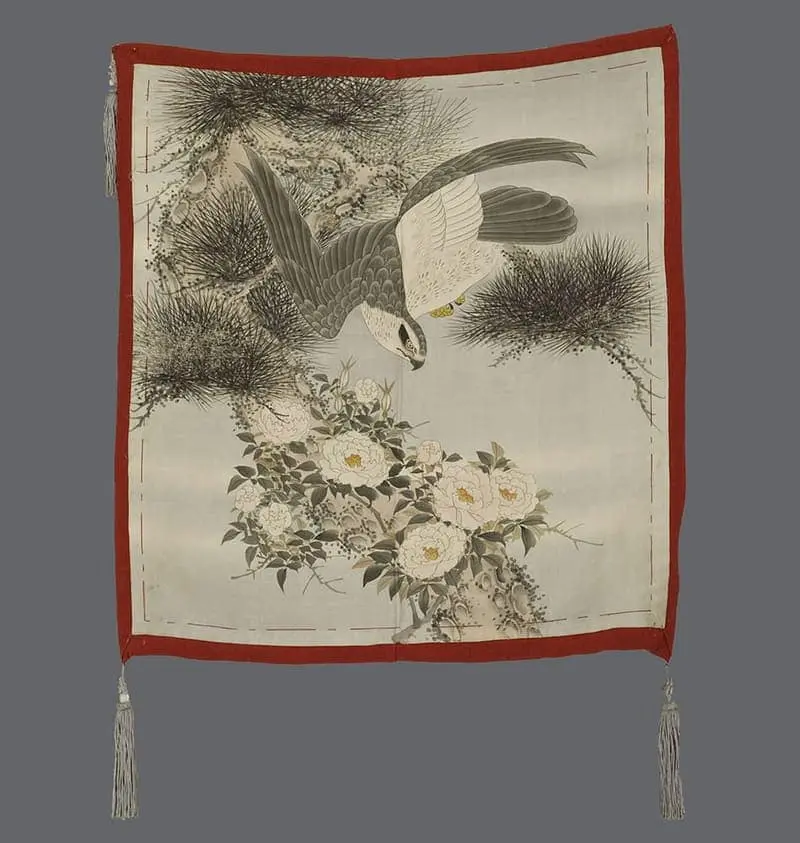

Fukusa are unique Japanese textiles traditionally used to cover gifts presented on wooden or lacquered trays during formal ceremonies. These art cloths, especially the type known as kake fukusa, are masterpieces of design, technique, and cultural symbolism. Created by specialized artisans using time-consuming methods, fukusa were not only functional items but also deeply meaningful symbols of respect, emotion, and social connection.

The practice of gift-giving in Japan is an ancient ritual, rooted in an agrarian society where mutual support and community ties were essential for survival. Gifts served as a means to strengthen social bonds, show appreciation, and promote goodwill. The fukusa, placed atop a gift, was integral to this ritual. Its presence transformed a material object into a meaningful gesture, communicating care, status, and sentiment without words. The act of covering a gift with a fukusa was itself a message—a display of respect and refined etiquette.

The tradition of using fukusa for gift presentation is believed to have begun in the 17th century. One of the earliest known examples dates to 1713 from the Konbuin Temple in Nara. Initially, this practice was exclusive to the aristocracy, especially the samurai and daimyo of Edo (Tokyo) and Kyoto. In these court cities, the rituals surrounding gift-giving were elaborate and steeped in hierarchy. As the merchant class grew wealthier in the 18th and 19th centuries, they adopted many of these noble customs, including the use of fukusa, as symbols of refinement and social aspiration.

During the Meiji Restoration in 1868, the feudal system was dismantled, and with it came the decline of samurai customs. However, the practice of gift-giving with fukusa endured, now more associated with prosperous merchants and urban elite. Even as modernization progressed, fukusa remained a part of key ceremonial events. Today, while no longer widely used, they still appear in formal occasions such as weddings, tea ceremonies, and corporate gift exchanges.

Gift-giving ceremonies followed a strict etiquette. Gifts were either delivered personally to the recipient’s home or exchanged at a neutral location. The fukusa-covered gift was placed on a tray and presented with a formal bow. Typically, the giver would offer an explanation of the gift, often using indirect language. The recipient, after receiving the gift, would examine the fukusa and its motifs carefully. This was a crucial part of the exchange, as the visual language of the fukusa conveyed unspoken emotions and intentions. Some days later, the gift tray and fukusa were usually returned to the giver, symbolically completing the cycle of respect and acknowledgement. Occasionally, prominent recipients kept the fukusa, indicating the high esteem in which they held the exchange.

The design of fukusa was tailored to the occasion, with motifs carefully chosen for their symbolism. For weddings, images of cranes, pine trees, and plum blossoms symbolized longevity and fertility. New Year’s fukusa might depict turtles or treasures associated with good luck. Coming-of-age ceremonies featured symbols of growth and maturity, while condolence fukusa conveyed themes of solace and transience. Other motifs related to birthdays, educational milestones, or seasonal festivals like Boys' Day, Girls' Day, and the Cherry Blossom Festival. Through these designs, the cloth itself became a powerful, silent expression of feeling.

Motifs were not just decorative but culturally rich symbols. Common themes included pine, bamboo, and plum (“Three Friends of Winter”), cranes and tortoises (longevity), cherry blossoms (ephemerality), and fans (celebration). Folklore, poetry, parables, and theater also informed many fukusa designs. Some included humorous puns, parodies, or allusions enjoyed as visual wordplay. This layering of meanings made the fukusa an object of intellectual and aesthetic engagement, a puzzle to be appreciated by both giver and recipient.

Artisans employed a variety of complex techniques to bring these motifs to life. Fukusa were usually made of silk, measuring between 20 to 44 inches square, with tassels on the corners to prevent direct contact with the fabric. The ‘face’ of the cloth displayed the primary artwork, while the reverse lining, often red or orange, was hidden beneath. Embroidery was among the most favored techniques, with gold or silver threads couched onto lustrous satin or crepe silk using fine stitches. This so-called "blue and gold" style, named for its frequent use of blue satin and gold thread, was particularly popular.

Other techniques included:

Yuzen-painting: a resist-dye method applied to crepe or plain-weave silk, comparable to painting on canvas.

Tsuzure-ori (slit-tapestry): a painstaking weaving method for intricate, colorful images.

Appliqué and cut velvet: rarer, but sometimes used for dramatic texture.

Koma-nui embroidery: couching metallic threads on stretched silk.

Various silk types were chosen to enhance the visual and tactile qualities of each piece. These included:

Shusu: smooth satin for bold embroidery.

Chirimen: crinkled crepe, ideal for dyed work.

Shioze: ribbed weave, used for both embroidery and dyeing.

Donsu and kinran: richly brocaded weaves, often gold-threaded.

The construction of a fukusa also mattered. Styles varied in how the lining was attached: some hid it completely (tachikiri awase), while others revealed the lining at corners (shihohi or yatsuzuma). In the 20th century, simplified forms like hikikaeshi became more common.

Fukusa evolved stylistically over time. In the 18th century, their appearance was often folk-art-like: simple layouts with scattered motifs and ample background. In the late Edo period (1800–1868), designs became denser and more narrative, drawing from kabuki theater, Chinese and Japanese legends, and seasonal imagery. The Meiji and Taisho periods (1868–1926) saw a shift to more realistic and intricate depictions, while the early Showa period favored machine-assisted brocades and modern themes.

Fukusa also changed in size. Eighteenth-century examples averaged about 68 cm by 64 cm. Sizes peaked during the early 19th century, then gradually shrank through the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods, reflecting changing tastes and practicality.

The presence of a mon (family crest) also offers clues to dating. Early fukusa rarely featured crests, but by the late Meiji period, they appeared more frequently, usually on the lining. Later, some crests were placed prominently on the face of the cloth.

.avif)