Sacred Threads: The Millennium-Long Evolution of Japanese Embroidery from Buddhism to High Art

Among the many textile arts that have flourished in Japan, embroidery stands as one of the most labor-intensive and prestigious embellishment techniques, ranking alongside shibori tie-dyeing, yuzen dye-resist painting, and bokashi shading in terms of complexity and cultural significance. The art of Japanese embroidery, known as 'shishu' or 'nui,' represents a remarkable journey of cultural adaptation and artistic evolution that spans over a millennium, transforming from imported religious art into one of the world's most sophisticated and aesthetically refined decorative techniques.

Ancient Origins and Buddhist Influence

Japan's history of embroidery traces back millennia, with archaeological evidence suggesting that early techniques involving basic stitching and simple embroidery were likely practiced in prehistoric times. However, these primitive forms bore little resemblance to the complex and sophisticated embroidery that would later define Japanese textile arts. The true foundation of Japanese embroidery as a refined art form began much later, marking a pivotal moment in the nation's cultural development.

The transformative period arrived in the 6th or 7th century, coinciding with one of the most significant cultural exchanges in Japanese history: the introduction of Buddhism from China. This religious and philosophical movement brought with it not only new spiritual concepts but also sophisticated artistic techniques that would profoundly influence Japanese culture for centuries to come. Among these imported arts was complex embroidery, a technique that had already reached remarkable levels of sophistication in Chinese Buddhist monasteries and workshops.

Initially, these imported embroidery techniques served primarily religious purposes, used to adorn altar cloths and other sacred textiles within Buddhist temples. The earliest knowledge of complex embroidery came directly through this religious channel, as Buddhist monks and artisans brought their skills and patterns to Japan along with their spiritual teachings. These early religious embroideries were characterized by their symbolic motifs, often featuring Buddhist iconography, lotus flowers, dragons, and other spiritually significant designs that served both decorative and devotional purposes.

The connection between embroidery and Buddhism was so strong that for several centuries, the most accomplished embroiderers were often associated with religious institutions. Temples became centers of learning where these techniques were preserved, refined, and passed down through generations of skilled artisans. The religious context provided both the motivation for excellence and the resources necessary to support the time-intensive process of creating elaborate embroidered works.

Cultural Adaptation and Artistic Evolution

As Buddhism became more deeply integrated into Japanese culture, the embroidery techniques that accompanied it began to undergo a remarkable transformation. Japanese artisans, renowned for their ability to absorb foreign influences while adding their own distinctive character, gradually modified and adapted these imported techniques to suit Japanese aesthetic sensibilities and practical needs. This process of cultural adaptation was not merely imitative but represented a genuine creative evolution that would ultimately produce something uniquely Japanese.

Over the centuries that followed the initial introduction of complex embroidery, Japanese craftsmen introduced numerous innovations and refinements that distinguished their work from its Chinese origins. They developed new stitching techniques, experimented with different thread materials and combinations, and created distinctly Japanese design motifs that reflected local flora, fauna, and cultural themes. The seasonal sensitivity that characterizes so much of Japanese art began to influence embroidery designs, with different motifs and color schemes deemed appropriate for different times of year.

By the time of the Edo period (1603-1868), Japanese embroidery had evolved into a refined art form that was arguably the most impressive in the world in terms of finesse and aesthetic appeal. The technical mastery achieved by Japanese embroiderers during this period was extraordinary, with artisans capable of creating works of breathtaking delicacy and complexity. The level of skill required to produce the finest examples of Edo-period embroidery represented the culmination of centuries of technical development and artistic refinement.

This golden age of Japanese embroidery was characterized by an unprecedented level of sophistication in both technique and design. Artisans developed methods for creating incredibly fine gradations of color and tone, techniques for producing three-dimensional effects that seemed to bring motifs to life, and approaches to composition that balanced complexity with elegance. The embroidery of this period was not merely decorative but represented a high form of artistic expression that could convey emotion, tell stories, and capture the essence of natural beauty.

Technical Mastery and Regional Specialization

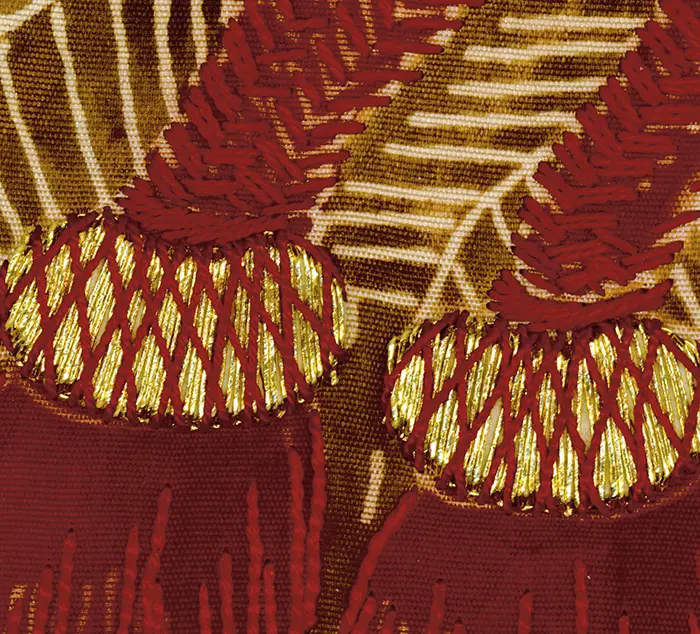

The technical sophistication of Japanese embroidery by the early 20th century encompassed a remarkable range of specialized techniques, each with its own characteristics and applications. Various embroidery styles flourished during this period, representing centuries of refinement and regional specialization. Among the most prominent techniques was 'sagara-nui,' equivalent to the French knot, which created small, raised circular elements that added texture and dimension to designs. This technique was particularly effective for creating the centers of flowers, the texture of tree bark, or the scales of fish and dragons.

'Sashi-nui,' employing long and short stitch techniques, allowed embroiderers to create smooth gradations of color and tone that could rival painted effects. This method was essential for creating realistic representations of natural subjects, such as the subtle color variations in flower petals or the graduated tones of sky and water in landscape motifs. The technique required exceptional skill to achieve seamless transitions between different colored threads while maintaining consistent tension and direction.

'Hira-nui,' or satin stitch, provided a method for creating smooth, lustrous surfaces that could fill larger areas with solid color while maintaining a refined appearance. This technique was particularly valued for its ability to create surfaces that caught and reflected light, adding luminosity to embroidered designs. The challenge of satin stitch lay in maintaining perfectly even tension and spacing across potentially large areas, requiring years of practice to master.

'Koma-nui' or 'kinkoma,' involving metallic thread couching, represented one of the most prestigious and technically demanding embroidery techniques. This method involved laying metallic threads on the surface of the fabric and securing them with tiny stitches, creating areas of brilliant metallic sheen that could represent everything from golden clouds to silver water. The technique required not only technical skill but also artistic judgment in determining the direction and pattern of the metallic threads to achieve the desired visual effect.

'Sugabiki,' which created fuzzy effects, added textural interest to embroidered designs by using techniques that produced soft, hair-like textures. This method was particularly effective for representing animal fur, certain types of flowers, or atmospheric effects like mist or clouds. The technique required careful control of thread tension and length to achieve the desired degree of texture without creating a messy appearance.

For many centuries, Kyoto maintained its position as the embroidery center of Japan, a tradition that persisted through the Taisho and early Showa periods. The city's status as the cultural capital of Japan, combined with its proximity to the imperial court and major temples, created an environment where the highest levels of artistic achievement were both demanded and supported. Kyoto's embroidery workshops became legendary for their skill and innovation, attracting the most talented artisans from across the country and setting standards that influenced embroidery production throughout Japan.

Aesthetic Advantages and Artistic Applications

Embroidery offered distinct advantages over woven patterns that made it particularly valuable for creating the most prestigious and visually striking garments. The technique allowed for extraordinary flexibility in color selection, enabling artisans to use any combination of colors without the limitations imposed by warp and weft structures in weaving. This freedom meant that embroiderers could create subtle color gradations, use colors that would be impossible to achieve in woven fabrics, and make adjustments to designs even as work progressed.

Perhaps most significantly, embroidery possessed the enchanting ability to create three-dimensional effects that brought designs to life in ways that flat woven patterns could not match. Through the use of varied stitch heights, different thread thicknesses, and layered techniques, skilled embroiderers could create motifs that seemed to rise from the fabric surface. Flowers could be made to appear as if they were about to bloom, birds could seem ready to take flight, and landscapes could be given a sense of depth and distance that rivaled painted artwork.

In early 20th century kimono, embroidery typically served to outline or highlight yuzen-created designs, creating a sophisticated interplay between different decorative techniques. This combination approach allowed designers to take advantage of the broad color washes and precise lines that yuzen could provide while using embroidery to add textural interest, dimensional effects, and areas of particular emphasis. The result was often garments of extraordinary complexity and beauty that showcased multiple traditional techniques in harmonious combination.

Embroidery was most commonly reserved for the most formal and expensive garments, reflecting both its labor-intensive nature and its association with the highest levels of craftsmanship. Uchikake wedding over-kimono, furisode long-sleeved kimono for unmarried women, and tomesode formal kimono for married women were the primary garments that featured extensive embroidery work. Although some kimono, mainly uchikake, had featured embroidery as the sole embellishment in earlier periods, this practice went out of favor during the Taisho and early Showa periods, when embroidery on wedding robes and furisode was always combined with other types of ornamentation.

In haori jackets from the 1920s and 1930s, embroidery often played a complementary role to yuzen-created designs, adding highlights and textural interest to already sophisticated painted backgrounds. This period saw some of the most successful combinations of different decorative techniques, as skilled designers learned to balance the various elements to create harmonious and visually compelling compositions.

The Embroidery Process: From Design to Completion

The creation of embroidered garments followed a carefully structured process that required both technical skill and artistic vision. Generally, the first step in kimono embroidery involved drawing the outlines of the design directly onto the silk cloth, using temporary marking materials that would not interfere with the final appearance. This preliminary drawing phase required considerable skill, as the proportions and placement of motifs had to be carefully calculated to work effectively on the three-dimensional form of the finished garment.

The next crucial step involved selecting the appropriate colored threads, a decision that took into account multiple factors including the intended season of wear, the wearer's age and social status, and the overall design concept. Thread selection was considered an art in itself, as subtle variations in color and sheen could dramatically affect the final appearance of the embroidered design. Master embroiderers developed an intimate knowledge of how different threads would interact with silk fabric and how colors would appear under various lighting conditions.

The actual embroidery work required the silk fabric to be stretched tight and secure on an embroidery frame, ensuring that the fabric remained properly tensioned throughout the stitching process. This step was crucial for maintaining consistent stitch quality and preventing puckering or distortion that could ruin the final appearance. The embroidery frame also allowed the artisan to work with both hands, one above and one below the fabric, enabling the precise control necessary for the finest work.

Hand-embroidering the stretched fabric demanded not only technical skill but also extraordinary patience and physical endurance. The most complex pieces could require months or even years of work, with artisans spending countless hours creating the minute stitches that would combine to form the final design. The physical demands of this work were considerable, requiring excellent eyesight, steady hands, and the ability to maintain consistent quality over extended periods.

The final steps in the embroidery process involved finishing touches that would enhance both the appearance and durability of the work. Excess threads on the reverse side were carefully cut off, ensuring that the back of the fabric remained neat and that loose threads would not interfere with the garment's construction or wear. The embroidered face was then covered in starch and smoothed with steam, a process that served multiple purposes: it made the embroidery threads shiny and more robust, helped set the stitches permanently, and gave the entire surface a refined, professional appearance.

Modern Developments and Continuing Legacy

Beginning in about the 1950s, a significant shift occurred in Japanese embroidery production as most commercial embroidery work began to be accomplished by machine rather than by hand. This transition reflected broader changes in Japanese society and economics, as the country modernized rapidly in the post-war period. While machine embroidery could produce attractive results much more quickly and at lower cost, it inevitably lacked the subtle variations and three-dimensional qualities that characterized the finest hand-embroidered work.

Despite this shift toward mechanization, the tradition of hand embroidery has not disappeared entirely. Master embroiderers continue to practice their craft, creating works for museums, collectors, and special occasions where the highest levels of artistry are still valued. These contemporary masters serve as links to centuries of tradition, preserving techniques and aesthetic principles that might otherwise be lost to modernization.

The legacy of Japanese embroidery extends far beyond its practical applications in garment decoration. The techniques developed over more than a millennium of refinement represent a sophisticated understanding of color, texture, and composition that continues to influence contemporary textile artists worldwide. The Japanese approach to embroidery, with its emphasis on subtle gradations, dimensional effects, and harmonious integration with other decorative techniques, offers lessons that remain relevant for modern designers and artists.

Today, Japanese embroidery is recognized internationally as one of the world's great textile arts, admired for its technical sophistication and aesthetic refinement. Museums around the world collect and display examples of Japanese embroidered garments, recognizing them not merely as clothing but as important works of art that represent centuries of cultural development and artistic achievement. The techniques that began as religious art in Buddhist temples have evolved into a sophisticated craft tradition that continues to inspire and influence artists across cultures and generations.

.avif)