Cultivating Longevity: Essential Practices for Antique Japanese Textile Care and Storage

Antique Japanese textiles, particularly the iconic kimono and haori, are more than just garments; they are tangible links to a rich cultural heritage, embodying centuries of artistry, craftsmanship, and social history. Each fold, every thread, and the intricate patterns tell a story of a bygone era, reflecting the aesthetics, technologies, and daily lives of their creators and wearers. However, these exquisite artifacts are inherently fragile, susceptible to degradation from environmental factors, pests, improper handling, and the passage of time itself. To ensure their survival for future generations, a meticulous and informed approach to their care and storage is not merely advisable but essential.

The first step in preserving any antique textile is to understand its fundamental composition. Japanese textiles, especially kimonos and haoris, are predominantly made from silk, a protein fiber renowned for its lustrous sheen, delicate drape, and vibrant dye absorption. While beautiful, silk is also highly vulnerable to damage. It can weaken and degrade when exposed to light, extreme temperatures, or fluctuating humidity. It is also a prime target for insect pests. Other common materials include cotton and linen, often used for more utilitarian kimonos or summer wear, which, while more robust than silk, are still susceptible to mold, mildew, and insect damage if not properly cared for. The dyes used, whether natural (like indigo or plant-based pigments) or early synthetic ones, vary in their lightfastness and can bleed if exposed to moisture. Furthermore, many antique pieces feature delicate embellishments such as embroidery, metallic threads, or intricate weaving techniques, all of which add to their fragility and require specialized attention.

Environmental control forms the cornerstone of textile preservation. Temperature and humidity are perhaps the most critical factors. Ideal conditions for textile storage are generally stable temperatures between 18∘C and 21∘C (65∘F and 70∘F), with relative humidity levels maintained between 45% and 55%. Fluctuations outside these ranges are far more damaging than stable, slightly suboptimal conditions. High humidity (above 65%) creates a breeding ground for mold and mildew, which can permanently stain and weaken fibers, and also attracts pests. Low humidity (below 35%) can cause fibers to become brittle and prone to cracking, especially silk. Extreme temperatures accelerate chemical degradation of fibers and dyes. Therefore, storing textiles in attics, basements, or against exterior walls, where temperature and humidity swings are common, must be avoided. Monitoring devices such as hygrometers and thermometers are indispensable tools for maintaining a stable environment.

Light, particularly ultraviolet (UV) radiation, is another significant enemy of antique textiles. Both natural sunlight and artificial light (especially fluorescent bulbs) contain UV rays that cause irreversible fading of dyes and weaken textile fibers, leading to embrittlement and eventual disintegration. For this reason, antique textiles should always be stored in complete darkness. If a piece is to be displayed, exposure should be strictly limited to short periods, ideally in a dimly lit space, and behind UV-filtering glass or acrylic. Rotating displayed pieces regularly can help minimize cumulative damage to any single area.

Air quality also plays a vital role. Dust, soot, and airborne pollutants (such as sulfur dioxide or nitrogen oxides from combustion) can settle on textiles, causing discoloration, abrasion, and chemical degradation. A clean storage environment is paramount. While some ventilation is good to prevent stagnant air, textiles should be protected from direct exposure to unfiltered air, which can carry pollutants and dust.

Handling antique textiles requires extreme caution and respect. Before touching any piece, ensure hands are clean, dry, and free of lotions, oils, or jewelry that could snag or abrade the fabric. Always support the entire weight of the textile when moving it, avoiding pulling on a single point or allowing it to hang unsupported, which can stress seams and fibers. Minimize handling as much as possible, as every touch introduces oils, dust, and potential for damage.

When it comes to cleaning antique textiles, the general rule is: do not attempt to wash them at home. Water, detergents, and even dry-cleaning chemicals can cause irreversible damage to fragile fibers, unstable dyes, and delicate embellishments. Dyes can bleed, silk can lose its sheen, and fibers can shrink or distort. For surface cleaning, gentle dusting with a soft, natural-bristle brush (like a hake brush) can remove loose dust. For more ingrained dirt, a specialized museum vacuum cleaner with low suction and a protective mesh screen placed over the textile can be used, but this should be done with extreme care. Any significant cleaning or stain removal should always be entrusted to a professional textile conservator who has the expertise and specialized equipment to assess the textile's condition and determine the safest treatment.

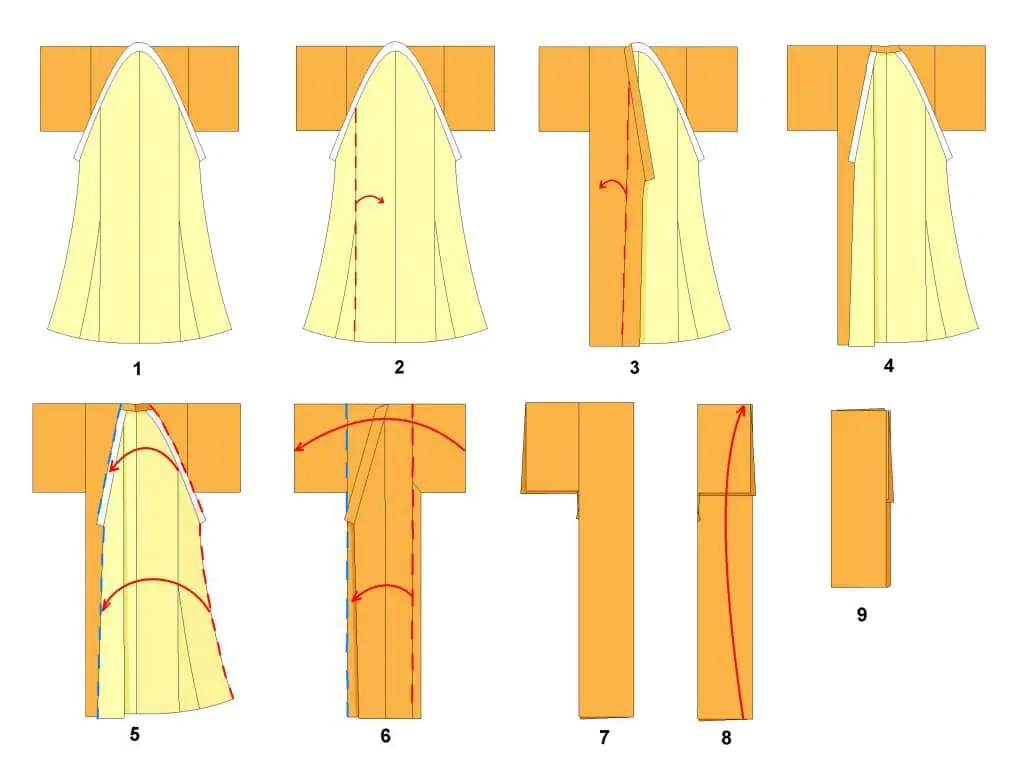

Proper storage methods are crucial for the long-term preservation of kimonos and haoris. Traditional Japanese folding, known as tatami-gata (or "tatami-style folding"), is an excellent method for kimonos. This method involves folding the garment along its existing seams and creases, creating a compact, rectangular package that minimizes stress on the fabric and allows for some airflow. It's a system designed to work with the garment's construction. For very fragile or heavily embellished pieces, or for long-term storage, rolling the textile around an acid-free tube (padded with acid-free tissue) can be preferable, as it avoids sharp creases that can weaken fibers over time.

The materials used for storage are just as important as the method. Only use acid-free, lignin-free archival materials. This includes acid-free tissue paper for interleaving folds and padding, and sturdy acid-free boxes. Unbuffered acid-free tissue is generally recommended for silk, as the alkaline buffering agents in buffered tissue can potentially react with silk over very long periods. For cotton or linen, buffered tissue can be used, but unbuffered is a safer choice for mixed textiles or if dye stability is uncertain. Textiles should be wrapped in unbleached cotton sheets or muslin, which allow the fabric to breathe while protecting it from dust. Avoid plastic bags or containers, as they can trap moisture, promote mold growth, and off-gas harmful chemicals that can damage textiles over time.

Pest control is an ongoing battle in textile preservation. Moths, carpet beetles, and silverfish are notorious for feeding on natural fibers. An integrated pest management (IPM) approach is best:

- Regular Inspection: Periodically inspect your textiles and storage area for any signs of pest activity (frass, casings, actual insects, or holes in fabric).

- Cleanliness: Keep storage areas meticulously clean and vacuumed.

- Avoid Attractants: Do not store food or plants near textiles.

- Natural Deterrents (with caution): While cedar and mothballs are commonly associated with pest control, they come with significant caveats. Cedar oils can stain textiles, and mothballs (naphthalene or paradichlorobenzene) are toxic, have a strong, persistent odor, and can also damage or stain fabrics with prolonged direct contact. Safer, non-toxic alternatives for small, localized issues might include sachets of dried lavender (though their deterrent effect is limited) or controlled freezing for small, unsoiled items (a process that must be done carefully to avoid condensation damage). The most effective pest control is vigilance and maintaining a clean, stable environment.

For textiles intended for display, ensure that the display period is limited. If using a mannequin or hanger, it must be properly padded to support the garment's weight evenly and prevent stress points. Rotate the textile regularly to distribute light exposure and stress on different areas. As mentioned, UV-filtering materials are essential for any display case.

Finally, recognizing when to seek professional help is paramount. If an antique Japanese textile is stained, torn, has active mold or insect infestation, or simply requires a thorough, safe cleaning, it is imperative to consult a qualified textile conservator. These specialists have the knowledge, tools, and experience to stabilize, clean, and repair fragile textiles without causing further damage, ensuring their long-term survival.

In conclusion, the care and storage of antique Japanese textiles, particularly kimonos and haoris, demand a commitment to proactive preservation. By understanding the vulnerabilities of their materials, meticulously controlling environmental factors, handling them with utmost care, and employing appropriate storage techniques, we can mitigate the ravages of time. These exquisite pieces are not merely fabric and thread; they are cultural treasures, and their diligent preservation is a profound act of respect for the artistry, history, and heritage they represent.

.avif)